“Look at the camera,” a Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officer told me as I approached the primary inspection point at the Paso del Norte port of entry.

“Is that the face recognition technology?” I asked. “If so, I want to opt-out.”

“Look at the camera.”

“I want to opt-out.”

“Look at the camera.”

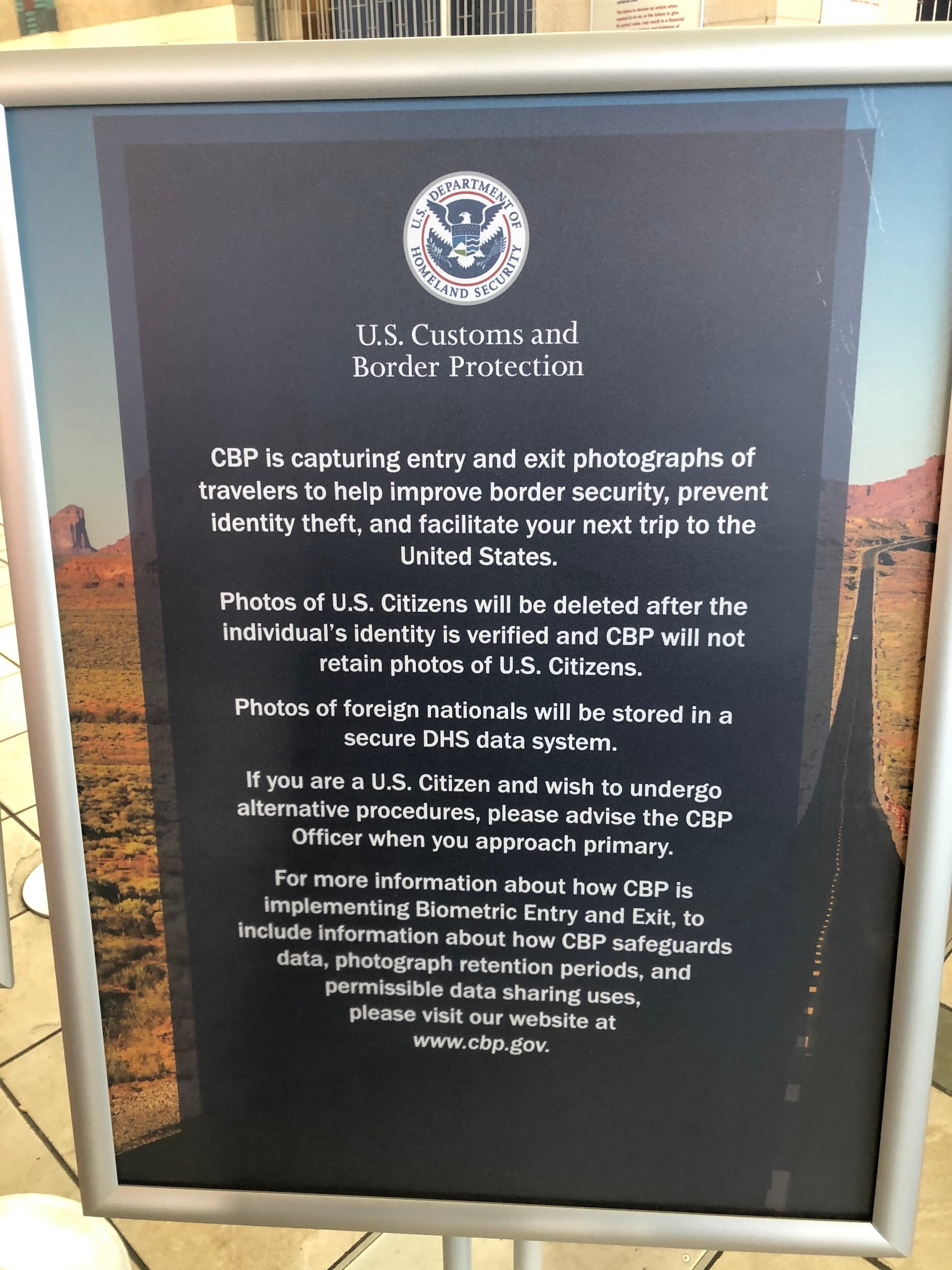

On the evening of November 25, 2019, I crossed from Mexico into the United States. Signs in the port noted the new use of face recognition technology and United States citizens’ option to “undergo alternative procedures.” After handing over my U.S. passport card, and despite my repeated protests, the CBP officer took my picture anyway.

My data was likely processed through a system of databases, handled by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), an agency with a long history of employing abusive surveillance techniques. In the last year, DHS has unlawfully tracked journalists and advocates, and was the subject of data breaches that exposed the private information, including photos, of thousands of travelers.

CBP, a component agency of DHS, began piloting the use of “biometric facial comparison,” or face recognition technology, in September 2018 at pedestrian crossing lanes in San Ysidro, California and vehicle lanes in Texas. On November 22, 2019, CBP announced the expansion of the technology to additional pedestrian lanes at ports in Texas, including the Paso del Norte port of entry in El Paso. This expansion came despite an internal review raising concern about the accuracy of such technology and despite serious problems identified by privacy experts about prior expansions at airports. The agency intends to expand the use of face recognition nationally at airports — despite the documented concerns.

CBP deploys a variety of surveillance technologies at the border, claiming national security justifications, but Congress has not explicitly authorized the use of face recognition technology in the immigration context. Congress has mandated that the DHS collect biometric information to track travelers entering and exiting the United States to identify those who overstay their visa, but fingerprints — and other less troubling methods — could achieve compliance without the worries surrounding face recognition.

Face recognition is one of the most dangerous forms of biometric tracking and carries a greater potential for growth into a widespread tool for spying on people as they move. Face recognition can be used for surveillance through public video cameras — mapping a person’s movement without their knowledge or consent and raising serious Constitutional concerns.

Photos collected by state motor vehicle agencies provide another source of data that could easily be coupled with face recognition to create a comprehensive surveillance system equipped to track U.S. citizens and immigrants alike throughout the country.

Given the many concerns and shortage of mechanisms to safeguard against abuse, immigration agencies should suspend their use of the technology at ports of entry.

CBP claims the technology will facilitate faster border crossings but the technology is inaccurate, exposing crossers to further inspection if the system falters. Studies also suggest the technology is racially biased, with error rates rising significantly when applied to people of color.

If I, carrying all the privilege of a white American lawyer, could not opt-out of the invasive technology, what chance do other travelers — and particularly people of color — have to assert their rights before an agency patterned on racial profiling and harassment? Indeed, many other travelers have been forced to submit to invasive face recognition — despite the agency’s promises that anyone can opt-out.

CBP clearly and consistently states that “it is not mandatory for U.S. citizens to have their photo taken” and if they wish to opt-out they should “advise the CBP officer when they approach the primary inspection area.” While no one should be subjected to this technology, CBP must minimally provide a meaningful opt-out option that does not mean hours of delay, and must train its agents on this policy. Even the best policies are meaningless if government agents are free to disregard them with impunity.

The CBP officer I encountered last week ignored my repeated protests, claimed ignorance of the signs plastering the port, and told me I could not opt-out. “Why are you so concerned? We have all your information anyway,” was the last thing the officer said before waving me through.

My concern is one we should all share: The continued expansion of surveillance technology at the border, under the guise of efficiency and security, signals the erosion of our privacy rights and the building of a system of government surveillance capable of intrusion in our everyday lives. Taking away every meaningful option to avoid new forms of surveillance simply cannot be an accepted border reality. The Constitution protects us all, even at the border.