Faces of Liberty: Standing Up for Religious Freedom

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…”

- First Amendment, Constitution of the United States.

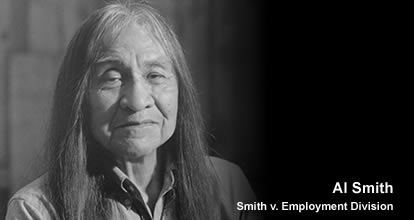

Al Smith was in his mid 50s — a recovering alcoholic who had picked himself up from the street, rebuilt his life, and made a career of helping others do the same — when he began reclaiming his Native American heritage. After almost half a lifetime without moorings, the ancient traditions that had been lost to him as a child became a growing source of spiritual comfort.

“I was spiritually unbalanced, I was starving. Now my spirit’s so happy. I’m on the high road, back to the Creator from whence I came.”

When he was seven, Smith was taken from the Klamath reservation by the federal Indian Agency and enrolled, like thousands of other Native American children, in a succession of boarding schools where, instead of big skies and open vistas, he found high fences, concrete yards and indoctrination into the white man’s culture. Memories of his own people’s ways were blotted out.

“They took us off, took me from my mother and my grandmother, and we were forbidden to speak our native tongue. They took away my freedom, and I couldn’t understand why I was locked up like that. We weren’t recognized as people. I was 55 or 56 years old before I attended my first Native American ceremony. I don’t speak Klamath. I know no Klamath songs.”

In 1983, Smith was fired from a job he held in Roseburg as a drug and alcohol counselor because he participated in the sacramental use of peyote, a controlled substance that, like the wine of Christian communions, is at the core of the centuries-old Native American religious ceremony in which Smith took part. Smith was denied unemployment benefits by the State of Oregon on grounds that his firing was for just cause. The confrontation inflamed the scars of the past.

“Is this going to continue on? Or am I going to put a stop to it, finally, and say: ‘You can’t tell me that I can’t go to religious ceremonies.”

Smith stood up for his rights-represented by Oregon Legal Services, with the aid of the ACLU. More than six years of litigation followed, culminating in a 1990 U.S. Supreme Court decision that affirmed the state’s denial of Smith’s unemployment claims.

“People have individual rights and they have be aware of that, to have the energy, the courage to speak out and question. Otherwise, we’ll fall into being just like a herd.”

Smith had only lost the battle, not the war. The Courts decision in Employment Division of Oregon v. Smith galvanized religious leaders of all faiths because it brazenly swept aside the long-held doctrine that government must show a “ compelling state interest” before infringing on religious practices. Oregon has since joined 23 other states and the federal government in declaring the sacramental use of peyote in Native American ceremonies legal. And President Clinton in 1993 signed into the law the restoring the “compelling interest” doctrine.

“I’m seeing to it that my little children - my daughter is twelve and my son is seven - have a choice about what path to follow. I didn’t have a choice. But they know the ceremonies. They know what a sweatlodge is. They’ve participated in a sundance. They know about the drum. So the culture is not lost.”

In June of 1997 the Supreme Court ruled the Religious Freedom Restoration Act to be unconstitutional and the law to be in violation of the first amendment. Regardless of the earlier disagreement in separationist ranks, one thing is generally agreed upon -- with the demise of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, pressure will now build on Capitol Hill to enact some for of "religion friendly" legislation. The most likely candidate is the Religious Freedom Amendment introduced by Rep. Ernest Istook.