STATE v WILLIAMS

December 15, 2016 - UPDATE: Today, Multnomah County Circuit Court denied Olan Williams a new trial in his challenge of the non-unanimous jury verdict returned in his felony criminal case.

ONLY TWO STATES ALLOW NON-UNANIMOUS JURIES TO DELIVER FELONY CONVICTIONS: OREGON AND LOUISIANA

by Mat dos Santos, Legal Director

We filed a friend-of-the-court brief in this case challenging the law for violating the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment of the United States Constitution

While the court ultimately denied Williams’ request for a new trial, the ruling goes to great length to explain the racist past of Oregon’s history generally, as well as concluding that race and ethnicity were motivating factors in the passage of Oregon’s non-unanimous jury law and that “the measure was intended, at least in part, to dampen the influence of racial, ethnic, and religious minorities on Oregon juries.”

November 23, 2016 - Anywhere else, a 10-2 jury vote means a hung jury. But not in Oregon or Louisiana. Here a 10-2 jury is enough to convict felony defendants. This morning, the ACLU of Oregon and the Oregon Justice Resource Center were in court supporting a challenge to the Oregon law that allows for non-unanimous jury convictions, arguing that it violates the Equal Protection Clause of the federal constitution.

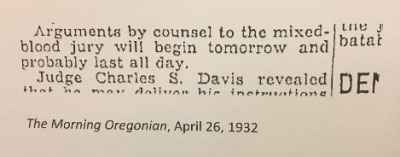

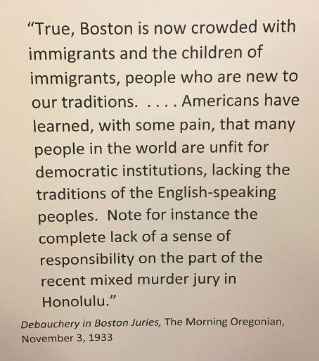

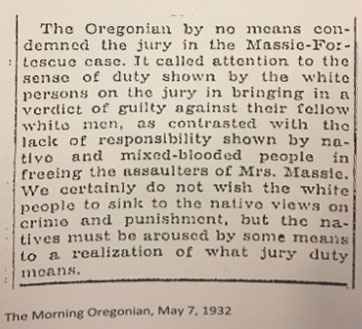

In both states, the laws allowing non-unanimous verdicts are steeped in racist and discriminatory intent. Oregon's constitutional amendment was born from xenophobia, while Louisiana's targets Black men.

In a state like Oregon where Whites make up the vast majority of the population, juries rarely get more than one non-white juror. So, under the law, Oregon courts may enlist non-white jurors, but they are then effectively locked out of the deliberation room. We filed a friend-of-the-court brief in support of defendant Olan Williams’ request for a new trial due to his conviction by a non-unanimous jury. Williams, a Black man, was convicted with one hold-out juror. The vote to acquit came from the only Black juror, but her voice and vote were silenced.

Studies cited by ACLU of Oregon and Oregon Justice Resource Center in their friend-of-the-court briefs show that jurors are more likely to convict a defendant of another race, due to conscious and unconscious prejudices, or what is known as implicit bias. Silencing minority jurors amplifies the effects of implicit bias as minorities are already significantly underrepresented in Oregon’s jury pools. Allowing non-unanimous jury verdicts functionally removes minority jurors altogether.

Jurors required to reach a unanimous verdict report being more satisfied and confident that they reached the correct verdict. When juries are not required to be unanimous, they tend to rush through their deliberations, taking fewer polls and ceasing deliberating when a quorum is reached, and take less time to reach a verdict.

Allowing non-unanimous jury verdicts silences minority voices, amplifies implicit bias, and perpetuates racial disparities. The discriminatory law that allows for non-unanimous juries goes against the heart of the American court system - that fundamental idea that all people have a right to a fair trial, judged by a jury of their peers.